Deathwatch: Deliver Them From Evil

Lionsgate Films, DVD, 2003

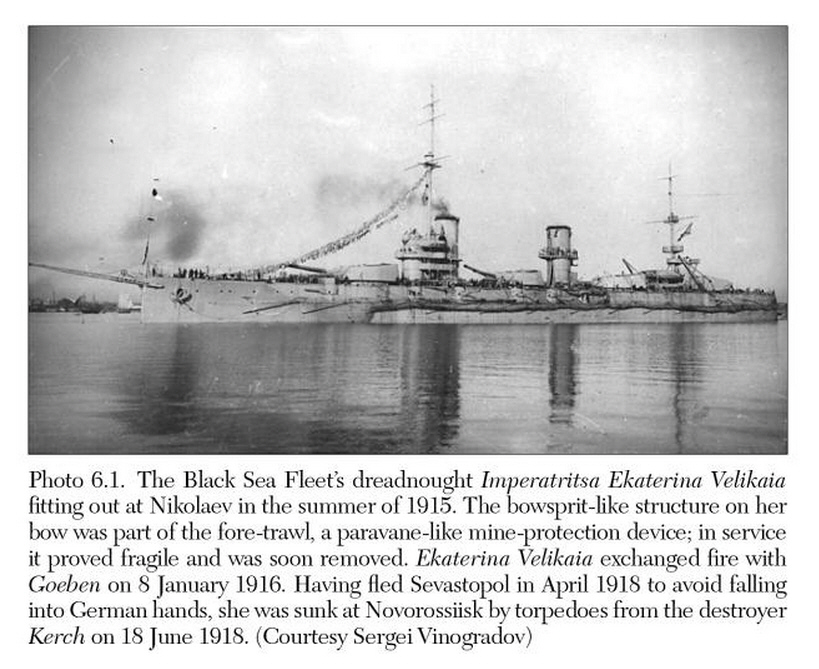

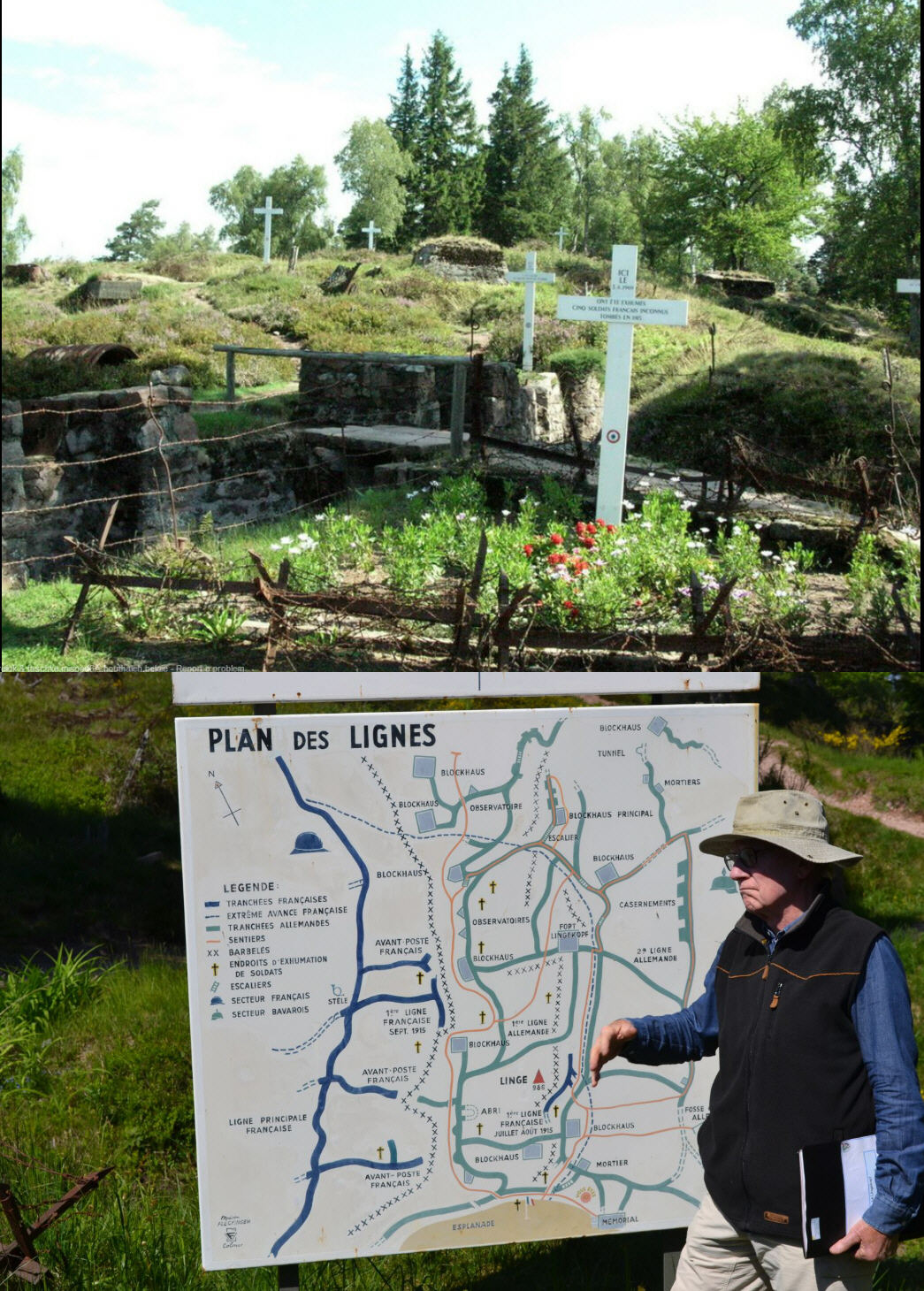

Deathwatch Does an Excellent Job Depicting the Standard Trench Warfare Scenery

Our regular contributor on literary

matters, David Beer – in his usual serious and insightful manner — has

contributed, a review of what is, to our mutual understanding, the only known

cross-genre World War One/ghoul film, Deathwatch, for our special

Halloween posting. David's review, which

focuses on the movie's religious implications, stands alone and is worthy of

your attention. However, after your

editor read the draft of the review, he came to the conclusion that David, who is

usually au courant with the latest

developments in popular culture, had overlooked (or chosen to avert his gaze

from) a dimension of the film that is part of a truly big phenomenon these days. His review sidesteps the "living dead,"

that is to say, the zombie, elements of Deathwatch. While

being a little subtle in its "Z" symbolism and avoiding any use of

the "Z" word in the script, Deathwatch,

nevertheless, has earned a place on various lists of "Best

Zombie" productions—right up there with Walking Dead, World War Z, and my personal

favorite, Zombieland. Since David passed

over the zombie clues in his review, your editor has supplemented his text below

with stills from the film that capture the film's zombie essence. MH

Review by David F.

Beer

This film brought to mind two lines from the last poem Isaac

Rosenberg wrote before he was killed in action. The poem, “Through These Pale

Cold Days,” describes suffering soldiers and states how "They see with living

eyes/How long they have been dead." This is about as close to a spoiler as I

want to go in discussing this horror film based on WWI. The surface plot is

easily described. A group of British soldiers go over the top at night into the

face of intense machine gun fire and exploding shells. Several standard trench

warfare motifs are provided: the fear before the attack, the youngest soldier

panicking and refusing to go over until threatened at gunpoint by an officer

and helped by a sympathetic comrade, tangles of barbed wire to negotiate or get

caught up in, mud containing bloated corpses, and the inevitable mowing down of

men by the enemy’s furious fire power.

The Corpses Have a Peculiar Look to Them, However

It’s almost unbelievable that anyone could live through such

a "stunt" but surprisingly the next scene shows a group of apparent survivors

trudging over no man’s land in thick fog that they mistake for gas. When they

discover it’s only fog and remove their masks, one soldier wonders what

happened to the night — he can’t understand how it suddenly became light. Apart

from the ominous and eerie background music we've heard from the beginning of

the film, this is the first hint we get that all is not normal. Further hints

will occur, however, such as a compass that no longer works, barbed wire that

seems to have a life of its own, and blood that seeps from the mud in the

German trench the survivors now occupy.

All but one of the Germans in the trench are dispatched

quickly enough, but not before it’s apparent that they are paralyzed with fear not of the British soldiers but of a nameless and invisible

force that has already been decimating them. They try to warn the British about

it but to no avail. Gradually it overcomes all but the youngest and most

innocent soldier, named Charlie Shakespeare, who in the end is able to leave

the dark trench and walk out into the light — but not before he glimpses all his

dead comrades sitting around a fire in a dark corner of the trench, seemingly

alive.

Motion Detected Among the Dead

To arrive at an understanding of what director/writer

Michael J. Bassett seems to have in mind in this film (and it’s admittedly open

to interpretation) we have to absorb numerous oblique hints. Why, for example,

is the subtitle of the film “Deliver them from evil”? Why the quick focus on a cross one of the

soldiers is wearing? What is the

significance of the Bible passage read over the pile of corpses? What are the ghostly

voices that are heard at one point above the trench? Why such comments by the

soldiers as "There’s so many dead," "God isn't here," "We are still alive," "We’re dead, Charlie, I know that now," and

Charlie Shakespeare’s exclamation as he leaves the trench after seeing all his dead

comrades sitting around a fire — "I’m not dead!"? And what do we make of the

German soldier at the very end waiting, with a knowing look in his eyes, for

the next squad of British soldiers who are about to occupy the trench?

Zombie Film Convention: The Living Dead Need a Shot to the Head to Be Truly Dead

Film enthusiasts will enjoy Deathwatch — even though it’s considered a fairly low-budget B

film — not only for its combination of supernatural horror mixed with a WWI

movie, but also for the parts played by actors such as Andy Serkis of Planet of the Apes and Lord of the Rings among other

accomplishments, by Jamie Bell as the young and decent Charlie Shakespeare who

had lied about his age to get into the army, and by Laurence Fox, whom I last

saw as Inspector Lewis’s assistant in the spin-off of the Inspector Morse series. No spoilers, or not too many, I hope, in

this short review, but I can’t help concluding with part of another poem this

film brought to mind — the opening lines of Wilfred Owen’s “Strange Meeting”:

It seemed that out of the battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since

scooped

Through granites which Titanic wars had

groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and

stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,—

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.

By David F. Beer (with a little help from the Editor)