|

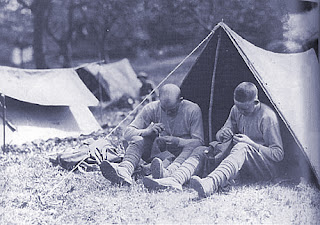

| Lt. Hoffman |

As it came to seem that America was being inexorably drawn into another world war, a veteran of the First World War published his stark recollections of the earlier struggle. His name was Robert "Bob" Hoffman (1897–1985). He had served with the 111th Infantry of the 28th Pennsylvania National Guard Division during the war and had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. After his war service he had settled in York, Pennsylvania, and became a weightlifting enthusiast and then a fitness entrepreneur, a rival to Charles Atlas. By 1940 he was successful and famous, and isolationist in outlook. He decided to sound a warning about what was ahead to his fellow countrymen and wrote a "pull-no-punches" recollection of his war experiences. The British newspaper The Independent published this slightly disjointed but powerful excerpt last year from I Remember the Last War (Strength & Health Publishing, 1940). One of Hoffman's duties was to command his unit's post-battle burial detail.

Our organisation lost men heavily from gas near here for they had two rather unpleasant assignments to perform. One was the burying of the dead soldiers who had lain for two or three weeks under the July sun, and the other was the digging up of dead Germans to remove their identification tags. In a wood nearby the soldiers were still lying who had helped stop the German advance toward Paris. They had sold their lives dearly in many cases, for a great many Germans had died too. Three weeks these men had lain in the sun and our troops set out to bury them. Americans and Germans alike were put under the sod.

There were horses too, and they were a problem. Horses are huge when they become bloated, swell to twice their normal size. Their legs are thrust out like steel posts and it requires a hole about 10ft square and 6ft deep to put a horse under. If the legs were off, a hole hardly more than half that size is required. At times we succeeded in using an axe and saw to cut off the horses’ legs. It was a hard task and an unpleasant one, but it had to be done.

Finally, the fields were cleared but there was still another gruesome task to perform. It is a law of war that the names of enemy dead be sent back through a neutral country to their homeland. The identification tags had been taken from the dead Americans but the Germans had been buried just as they were. There was the task to dig them up again – enough to remove half of their oval-shaped identification tags. That was a much more disagreeable job than the first.

Gas came over, and owing to the terrific odour even the powerful-smelling mustard gas could not be detected. Our men were working hard in the mid-July heat, perspiring, just in the right condition for mustard gas. Nearly half the remainder of our company, 67 in all, were gassed badly enough to be sent to the hospital. Many of them died; most of them were out for the duration of the war…

Did you ever smell a dead mouse? This will give you about as much idea of what a group of long-dead soldiers smell like as will one grain of sand give you an idea of Atlantic City’s beaches.

A group of men were sent to Hill 204 to make a reconnaissance, to report on conditions there as well as to bury the dead. The story was a pathetic one. The men were still lying there nearly two weeks later just as they had fallen. I knew all of these men intimately and it was indeed painful to learn of their condition. Some had apparently lived for some time, had tried to dress their own wounds, or their comrades had dressed them; but later they had died there…

Many of the men had been pumped full of machine-gun bullets – shot almost beyond recognition. A hundred or so bullets, even in a dead man’s body, is not a pretty sight. One of our men was lying with a German bayonet through him – not unlike a pin through a large beetle … The little Italian boy was still lying on the barbed wire, his eyes open and his helmet hanging back on his head. There had been much shrapnel and some of the bodies were torn almost beyond recognition. This was the first experience at handling and burying the dead for many of our men. It was a trying experience … The identification tags removed from the dead were corroded white, and had become embedded in the putrid flesh. Even after the burial, when these tags were brought back to the company, they smelled so horribly that some of the officers became extremely sick …

There are two chief reasons why a soldier feels fear: first, that he will not get home to see his loved ones again; but, most of all, picturing himself in the same position as some of the dead men we saw.

|

Pennsylvania Historic Marker

York, PA |

They lay there face up, usually in the rain, their eyes open, their faces pale and chalk-like, their gold teeth showing. That is in the beginning. After that they are usually too horrible to think about. We buried them as fast as we could – Germans, French and Americans alike. Get them out of sight, but not out of memory. I can remember hundreds and hundreds of dead men. I would know them now if I were to meet them in a hereafter. I could tell them where they were lying and how they were killed – whether with shell fire, gas, machine gun or bayonet …

The first dead man I touched was Philip Beketich, an Austrian baker who was with our company. He was wounded in the Battle of Fismes. I had tried to save his life by carrying him through the heavy enemy fire and putting him in one of the cellars of the French houses. He was shot in my arms as I carried him. A few hours later I found time to go round and find how he was. He was dead – stiff and cold … I had to remove his identification tags, and they had slipped down between his collar bones and the flesh of his chest. They were held there, and it took an effort to get them out. I thrilled and chilled with horror as I touched him.

Just a bit later I had to touch my very good friend Lester Michaels, a fine young fellow who had been a star football player on our company team, and a good piano player who entertained us when such an instrument was available. He went walking past me in Fismes, bent well over. “Keep down, Mike,” I said. “There’s a sniper shooting through here.”

Just then Mike fell, with a look of astonishment on his face. “What’s the matter, Mike?” I asked.

He replied: “They’ve got me,” shook a few times and lay dead upon his face with his legs spread apart – shot through the heart.

He lay there for more than a day. There was a terrific battle on and we had no chance to help the wounded – certainly not the dead. I was running short of ammunition and I needed the cartridges in Mike’s belt. I tried to unfasten his belt, but I could not reach it.

Finally I had to turn him completely over. It was quite an effort owing to the spread-eagle manner in which he lay. His body was hard and cold, and I saw his dead face – difficult to describe the feeling I had. But necessity demanded that I unloosen his belt and take his ammunition and still later his identification tag. After the war I heard from his relatives who wanted to know exactly how he had died.

There are many people who sought this information. They liked to know whether the soldier was killed by shell fire, whether while fighting hand to hand, while running to the attack, or in some phase of defensive work. It was hard to touch these dead men at first.

My people at home, hearing of what I was passing through, expected me to come back hard, brutal, callous, careless. But I didn’t even want to take a dead mouse out of a trap when I was home. Yet over there I buried 78 men one morning.

I didn’t dig the holes for them, of course, but I did take their personal belongings from them to return to their people – their rings, trinkets, letters and identification tags. They were shot up in a great variety of ways, and it was not pleasant, but I managed to eat my quota of bread and meat when it came up, with no opportunity to wash my hands.